Research

Individuals and populations do not exist in a vacuum; they exist and evolve in a complex network of ecological interactions. In the COMMONS lab we are interested in how, as organisms evolve, they transform their interactions and how these ecological changes feed back in the evolutionary dynamics and trajectories of populations and communities.

Overall we are trying to understand (and potentially predict) the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of microbial communities. The main idea is to understand cells and their physiology as they exist in relationship with the environment and other cells. To accomplish this, we often (but not exclusively) work with self-assebled microbial communities in relatively simple environments where we can understand their function and physiology without removing the context and interactions that are central to this functioning.

The problem is to construct a third view, one that sees the entire world neither as an indissoluble whole nor with the equally incorrect, but currently dominant, view that at every level the world is made up of bits and pieces that can be isolated and that have properties that can be studied in isolation. Lewontin (Biology as ideology)

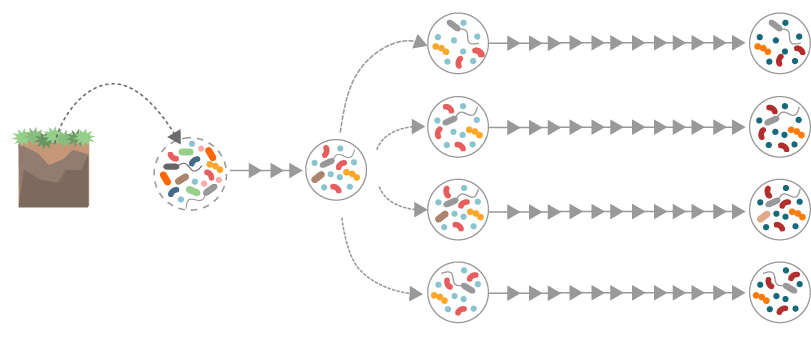

Historical contingency and predictability of ecological and evolutionary dynamics

In a rapidly changing world, we would like to predict the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of populations and communities. But both ecology and evolution are historical sciences and as such, trajectories are often contingent on previous steps. This “historical contingency” is often considered a source of unpredictability because small stochastic differences in mutations or species sampling could lead to very different outcomes. However, selection could override those small differences over time. Thus, we are interested in understanding:

- How and when do past changes shape future ecological and evolutionary trajectories?

- When do small stochastic differences get amplified, and when is selection able to override the effects of historical contingency?

- What kind of ecological and evolutionary changes open novel trajectories and which kind of changes and interactions canalize future responses?

- To what extent and at what scales are we able to predict ecological and evolutionary trajectories of microbial communities?

Microbial evolution within communities

Microbes are often found in complex multi-species communities. Interactions between species within a community can affect function and stability and can have important effects on the ecosystem as a whole. However, most of our understanding of microbial evolution comes from single strains, or pairs of interacting microorganisms, but most communities include multiple types of interactions and different degrees of dependency between members of the community. We do not understand how community context affects microbial evolution, nor the impact of these evolutionary changes on community dynamics. Even in simple systems, with strong selection and a simplified ecology, evolutionary change can increase ecological complexity leading to distinct outcomes. So, how do eco-evolutionary feedbacks affect our ability to predict short and long term dynamics?

Evolution of metabolic architectures and their ecological, and evolutionary consequences

Metabolism mediates bacterial interactions, responses to their environment, and fitness; it also determines the function of microbial communities and their impact on the ecosystem. Overall, new metabolic structures are hard to evolve (less so their regulation) and therefore metabolic structure provides some constraints and rules that can aid in the predictability of evolution. In the COMMONS lab, we are interested in exploring:

- How and when are new metabolic structures expected to evolve?

- What are the ecological and evolutionary consequences of metabolic innovation?

- Can we use metabolic constraints to predict community assembly and evolutionary change?

Multiple levels of selection and directed evolution of microbial communities

Selection can act on very different entities and at a different levels (genes, whole cells, multicellular organisms, …) as long as there is heritable variation in the reproductive success of such entities. However, selection tends to not be as efficient at higher levels of organization because at these levels there tends to be less heritable variation, smaller population sizes, and longer generation times. Inheritance, reproduction, growth are all evolved (and evolving processes), and we are interested in how these processes evolve at different levels, and how they affect evolutionary dynamics. Finally, we are collaborating with the Sanchez lab to develop and test a theory of how can we use selection to improve microbial community functions of interest.

Effects of microbial communities on plant fitness and evolution

Microbial interactions between plants and microbes affect plants’ resource acquisition, resistance to drought and disease, plant phenology, and interactions with herbivores and pollinators. Thus, plant microbe-associations might be an important avenue for adaptation to climate change. However, the significance of microbes for plant evolution is still poorly understood. We are studying how microbes might affect plant plasticity and development, how plant traits and heterogeneity within and between plants affects microbial community composition and the potential feedback of these processes on plant evolution.

Our ways of doing science, and what microbes can teach us about ourselves

Science is a way to look at the world, one that has a lot of influence in our society. As such, the ways we do science reflect things about ourselves, our society, and our material conditions. Reflecting on scientific practices can allow us to be more intentional.